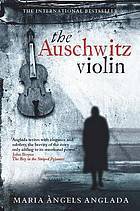

As regards books, I’m starting into the year 2018 on a rather sad note. This is because I dedicate this whole month to the horrors of the holocaust and World War II in Eastern Europe as they come to life through the very different stories of four survivors, ones real, others more or less fictionalised, if not fictitious. Three of the four books on my blogging schedule of January have protagonists who devoted their lives to music. The novel that I picked for my first review of the year evokes the literally life-saving craftsmanship of a young Jewish violin maker in a small subcamp of Auschwitz. When the camp commander finds out that Daniel is a luthier, he orders him to make The Auschwitz Violin following a bet with the sadistic camp doctor. Not knowing that his life is even more at stake than usual, Daniel plunges into the work he loves.

As regards books, I’m starting into the year 2018 on a rather sad note. This is because I dedicate this whole month to the horrors of the holocaust and World War II in Eastern Europe as they come to life through the very different stories of four survivors, ones real, others more or less fictionalised, if not fictitious. Three of the four books on my blogging schedule of January have protagonists who devoted their lives to music. The novel that I picked for my first review of the year evokes the literally life-saving craftsmanship of a young Jewish violin maker in a small subcamp of Auschwitz. When the camp commander finds out that Daniel is a luthier, he orders him to make The Auschwitz Violin following a bet with the sadistic camp doctor. Not knowing that his life is even more at stake than usual, Daniel plunges into the work he loves.Maria Àngels Anglada was born in Vic, Catalonia, Spain, in March 1930. After the Spanish Civil War she studied Classical Philology at the University of Barcelona specialising in Greek mythology, but giving special attention to Catalan and Italian poetry too. Along with teaching and doing at university, she wrote essays, translated Latin and Greek classics into Catalan, retold ancient Greek myths for children, and collaborated assiduously with different literary journals. In 1972 she and the poet Núria Albó published together a volume of poetry which she followed up with two others entirely her own in 1980 and 1990. In 1978 she made her successful debut as a novelist with award-winning Les closes (The Fences). Until her death the author brought out several more novels, namely Viola d'amore (1983; Viola d’Amore), Sandàlies d'escuma (1985; Sandals of Froth), Artemísia (1989), L'agent del rei (1991; The King’s Agent), The Auschwitz Violin (El violí d’Auschwitz: 1994), and Quadern d’Aram (1997; Aram’s Notebook), along with two collections of short stories. Maria Àngels Anglada died in Figueres, Catalonia, Spain, in April 1999.

It’s during a concert in Krakow in December 1991 that the violinist Climent hears for the first time the beautiful tone of The Auschwitz Violin. The woman who plays it is Regina Strinasacchi, the first violinist of the orchestra that invited him and his trio to Krakow for the concert and classes at the Academy of Music. Wondering who may have made the remarkable instrument, he asks its owner the following day and she willingly tells him that it’s her Uncle Daniel’s work, but her body language makes it clear to him that a very sad story must surround it.

“What could a luthier, a violin maker, do in hell? “Carpenter” had seemed like a good answer at the time, even to the official who registered the information with an approving nod. Always a need for one. But after a few harrowing months, which had seemed more like years, Daniel was no longer certain. […]”The small lie about his occupation put Daniel into a privileged position among the inmates of the small Auschwitz subcamp Dreiflüsselager because the carpenters are always doing odd jobs around the Commander’s house and are spared the quarry. One day Daniel is called to repair a minute defect on a door, while three fellow inmates rehearse for a concert. When the Commander abuses the violinist for a mistake, Daniel intervenes and explains that his violin has a small crack on the top plate that he could easily fix. In a whim the Commander orders him to do the repair overnight.

“He was himself once again, not a number, not an object of taunting ridicule. He was Daniel, a luthier by profession. At that moment he thought of nothing other than the job at hand and the pride he took in it. His eyes glistened with precise attention; even his hunger disappeared. […]”The next morning the Commander approves the provisional repair and Daniel learns that the violinist has been punished after all. Back in the carpenters’ workshop Daniel feels miserable and fears that he might still pay dearly for having addressed the Commander without permission. Instead, he is ordered to craft a violin “like the Stradivarius” and is given everything needed. Later the violinist with whom he makes friends tells him that the Commander bet with the cruel camp doctor that he could make a new instrument within a set time. Daniel puts his heart and remaining strength into the task.

Like parentheses a first-person plot set in the novel’s present of the early 1990s frames the chapters that contain the main plot surrounding The Auschwitz Violin and the survival of its maker from the point of view of an omniscient third-person narrator. Quotes from different classical sources introduce most of the chapters and presage their dominant atmosphere. In addition, translated extracts from authentic Nazi files concerning conditions in the concentration camps at the beginning of most chapters anchor the plot in reality although it’s pure fiction. At least to my knowledge, no violin has actually been made in any of the numerous Nazi concentration camps notwithstanding that several inmates survived the horrors thanks to playing an instrument. Both the story of the luthier and his character seem perfectly convincing to me, but I reckon that only the survivor of a Nazi concentration camp is in the position to really judge. Nonetheless, I dare say that the novel stands comparison even with some holocaust memoirs that I read. The novel’s English translation by Martha Tennent had a gentle flow that carried me towards a slightly forced happy ending and that it may well owe to the quality of the Catalan original.

Having a strong interest in history, notably in the era of Hitler’s Third Reich, which fortunately lasted only little more than a decade in the end, I really liked The Auschwitz Violin by Maria Àngels Anglada. It’s not a novel that I’d feel comfortable calling pleasurable or even entertaining, but it definitely was captivating and touching. Moreover, it was a quick read just right for a gloomy winter afternoon cuddled up by the heating with a pot of hot tea by my side to sip now and then… and nothing to nibble because it would have felt shameless with such a book. It’s a good addition to my small collection of holocaust novels and memoirs containing important works like Fatelessness by Kertész Imre or Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor E. Frankl (»»» read my review), to name just one of each. At any rate, this slim volume too deserves my recommendation.

For several years I have done a post in observation of International Holocaust Day, held on January 27. Last year i posted on a nonfiction work, the Jewish History Work of the Year Award Winner very tied into your post

ReplyDeleteInternational Holocaust Day is an observation of the six million Jews who were murdered during the Holocaust. The Holocaust can be seen in many ways. I have posted on a number of Holocaust related works as well as classic works of Yiddish literature. I see the Holocaust as a war on the reading life. Never has there been a culture more dedicated to the absorption of the written war than that of Central European and Russian Jews. First the Nazis burned their books, then their bodies. There is no totalitarian group in the world that is not Anti-Semitic. Being anti- Jewish and Anti-Semitic should be understood as related but separate things, both repugnant. To me the Holocaust is made somehow personal by the death at 42 of one of my most beloved authors, Irene Nemirovsky who died a month after arriving at Auschwitz.

This is my second year posting in observation of this day. Not just Jews died in the Holocaust and I hope one day there will be a greater awareness of this.

Violins of the Holocaust-Instruments of Hope and Liberation in Mankind's Darkest Hour by James A. Grymes tells the story the violins played by Jewish musicians during the Holocaust. He writes in a very illuminating fashion about the importance of the violin in Central and Eastern European Jewish culture. The book focuses on the twenty years the famous Israeli violin restorer Annon Weinstein spent working on these violins. Grymes tells the story, some of survival aided by the violins and some of death of the men who played them. Along the way we learn of the genesis of classical music in Israel.

Thanks four your long expert comment, Mel! It was in the back of my mind that the Auschwitz concentration camp was liberated by the Red Army on a day in January, but I wasn't aware that it's at the same time the International Holocaust Day. I'm glad that you drew my attention to it.

DeleteIt's true that many important European authors were victims of the holocaust - be it directly like Irène Nemirovky, Janusz Korczak, or Antal Szerb, be it indirectly like Stefan Zweig who killed himself in Brasilian exile.

The books you named sound very interesting. I had heard of the orchestra in the Theresienstadt Ghetto and I knew that there were orchestras in the great concentration camps like Auschwitz, but I never thought of the role they may have played later on in Israel and elsewhere. Doing a bit of research I found a website Music and the Holocaust. It gives an interesting introduction into the topic.

I commend your dedication and theme this month. And look forward to your coming reviews of novels with protagonists who devoted their lives to music.

ReplyDeleteOnly three of four have devoted their lives to music and two of the books are re-blogs because I no longer write weekly reviews. However, I hope that you'll like the novels that I picked :-)

DeleteThis one sounds good. Thanks for the review.

ReplyDeleteMy pleasure, Becky!

Deletewww.byutv.org at Christmas has a movie they showed called "Instrument of War".

ReplyDeleteIt's a true story movie about a violinist who builds a violin in a Concentration Camp. It's a great movie!