The steadily growing divide between rich and poor isn’t a new phenomenon, or else Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels would never have had reason to write the Communist Manifest and the blood-soaked October Revolution of 1917 might never have massacred the Russian Tsar along with his family to put the idealistic principles of Marxism into practice. During the first decades of the new regime, people worldwide dreamt of following the country’s example unawares of the fact that Lenin, Stalin and their likes turned their egalitarian Soviet utopia into the dystopian oligarchy, even monocracy of totalitarian Bolshevik leaders. Set in the working-class district Brás in São Paulo, Brazil, the proletarian novel Industrial Park by Patrícia Galvão, first published under the pseudonym Mara Lobo in 1933, shows the daily struggles of women who have to cope not just with cutthroat capitalism but also with machismo. The communists among them call for fight…

Please help me spread information on good literature. In other words: please consider sharing a post that you like. Thank you!

Showing posts with label Latin American literature. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Latin American literature. Show all posts

Friday, 31 January 2020

Friday, 30 August 2019

Book Review: To Bury Our Fathers by Sergio Ramírez

It’s people who make history by way of passing on knowledge about the more or less heroic deeds of individuals and groups to later generations not just through different memorabilia, but also as stories that over time may even turn into legends. Above all, turbulent times that are exceptional with regard to what people have to go through and bear with – be they wars or revolutions, be they periods of voluntary or forced migration, just to give a few examples – are a hotbed for such stories. And wherever people come together it’s likely to hear the one or other of them like in To Bury Our Fathers by Sergio Ramírez, a Nicaraguan novel from the 1970s that evokes from different perspectives the country’s (or actually the whole region’s) tragic that is history marked by terror regimes and armed resistence with or without the meddling of the USA and the USSR.

It’s people who make history by way of passing on knowledge about the more or less heroic deeds of individuals and groups to later generations not just through different memorabilia, but also as stories that over time may even turn into legends. Above all, turbulent times that are exceptional with regard to what people have to go through and bear with – be they wars or revolutions, be they periods of voluntary or forced migration, just to give a few examples – are a hotbed for such stories. And wherever people come together it’s likely to hear the one or other of them like in To Bury Our Fathers by Sergio Ramírez, a Nicaraguan novel from the 1970s that evokes from different perspectives the country’s (or actually the whole region’s) tragic that is history marked by terror regimes and armed resistence with or without the meddling of the USA and the USSR.

Labels:

1970s,

book reviews,

fiction,

Latin American literature,

novels

Friday, 28 June 2019

Book Review: Hell Has No Limits by José Donoso

Ever since scientists first expounded their theory of evolution, those in power gladly have been taking recourse to the concept of the survival of the fittest to justify even their most selfish actions before themselves. Unquestionably, the urge to exercise power over others belongs to human nature, but often it brings forth the worst in a person. Less settled characters even seem to think that it were their inborn right to bully those who are weaker than themselves and defenceless. In the 1960s Chilean classic Hell Has No Limits by José Donoso the homosexual transvestite living in a small rural brothel is regularly teased and beaten up by the clients because her mere presence provokes them. For nearly twenty years she has been co-owner together with the girl whom he fathered in the night when she agreed to help the Madame win a wager pretending to have sex with her.

Labels:

1960s,

book reviews,

fiction,

Latin American literature,

novels

Friday, 1 February 2019

Book Review: The Republic of Dreams by Nélida Piñon

Since times immemorial people have been dreaming and telling stories. Ancient myths and legends are part of the cultural heritage that shapes our view of the world and helps us to cope with life. But as we grow older the longing to live our own adventures and to weave our own legends grows. Determined “to make the Americas” thirteen-year-old Madruga, the central character of The Republic of Dreams by Nélida Piñon, left his native Galicia and arrived in Brazil in 1913. By the early 1980s, he is head of a numerous family and of a profitable group of companies, but almost lost his beloved grandfather’s ancient Galician legends. When his wife announces that death is coming for her, he and all the people who are integral part of their lives look back on the memorable events, joys and tragedies of seventy years thus start a new – Brazilian – legend.

Since times immemorial people have been dreaming and telling stories. Ancient myths and legends are part of the cultural heritage that shapes our view of the world and helps us to cope with life. But as we grow older the longing to live our own adventures and to weave our own legends grows. Determined “to make the Americas” thirteen-year-old Madruga, the central character of The Republic of Dreams by Nélida Piñon, left his native Galicia and arrived in Brazil in 1913. By the early 1980s, he is head of a numerous family and of a profitable group of companies, but almost lost his beloved grandfather’s ancient Galician legends. When his wife announces that death is coming for her, he and all the people who are integral part of their lives look back on the memorable events, joys and tragedies of seventy years thus start a new – Brazilian – legend. Friday, 10 November 2017

Like Water for Chocolate by Laura Esquivel

In our modern western culture we – women and men alike – claim for ourselves the right to be the architects of our individual future… and happiness, but it’s a rather recent achievement even for us. During the greater part of history here too the lives of people were by and large determined by others, notably by fathers, feudal lords, priests, Kings or Queens, and by seldom questioned unwritten rules. Individual happiness mattered very little, romantic love was of no importance in marriage matters. In Mexico of the early twentieth century the protagonist of Like Water for Chocolate by Laura Esquivel is supposed to willingly uphold tradition that demands of her as the youngest daughter to put last her own longing for happiness in marriage and to take care of her mother until she dies. Love is stronger than tradition, though, and the girl’s passion for cooking accompanies her on her painful and long way to empowerment.

In our modern western culture we – women and men alike – claim for ourselves the right to be the architects of our individual future… and happiness, but it’s a rather recent achievement even for us. During the greater part of history here too the lives of people were by and large determined by others, notably by fathers, feudal lords, priests, Kings or Queens, and by seldom questioned unwritten rules. Individual happiness mattered very little, romantic love was of no importance in marriage matters. In Mexico of the early twentieth century the protagonist of Like Water for Chocolate by Laura Esquivel is supposed to willingly uphold tradition that demands of her as the youngest daughter to put last her own longing for happiness in marriage and to take care of her mother until she dies. Love is stronger than tradition, though, and the girl’s passion for cooking accompanies her on her painful and long way to empowerment.Friday, 14 July 2017

The Green Pope by Miguel Ángel Asturias

It’s not a particularly secret wisdom that those who have wealth are likely to have power too. After all, it’s money that makes the world go round… at least a materialistic world like ours. Little wonder that our society produces considerable numbers of men and women whose primary goal in life is to gain money and ever more money. In The Green Pope by Miguel Ángel Asturias, Guatemalan winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature 1967 “for his vivid literary achievement, deep-rooted in the national traits and traditions of Indian peoples of Latin-America”, a young American who cares for nothing but wealth and power starts a banana plantation in Guatemala mercilessly ruining, driving out or even killing small local farmers and opponents on his rise. Neither the suicide of his fiancé, the death of his wife in childbirth or the pregnancy of his unmarried daughter make him reconsider his priorities.

It’s not a particularly secret wisdom that those who have wealth are likely to have power too. After all, it’s money that makes the world go round… at least a materialistic world like ours. Little wonder that our society produces considerable numbers of men and women whose primary goal in life is to gain money and ever more money. In The Green Pope by Miguel Ángel Asturias, Guatemalan winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature 1967 “for his vivid literary achievement, deep-rooted in the national traits and traditions of Indian peoples of Latin-America”, a young American who cares for nothing but wealth and power starts a banana plantation in Guatemala mercilessly ruining, driving out or even killing small local farmers and opponents on his rise. Neither the suicide of his fiancé, the death of his wife in childbirth or the pregnancy of his unmarried daughter make him reconsider his priorities.Friday, 31 March 2017

Book Review: Água Viva by Clarice Lispector

According to scientists specialised in the workings of the brain, the present lasts no longer than three seconds. Certainly, when we say “now”, we seldom think of it as such a short period of time, but language is necessarily imprecise and in addition meaning changes with context as well as with people concerned. Nonetheless, we may agree on it that the present is nothing but a fleeting moment that separates past and future… and it’s all that we actually have. Everything else only exists as an idea in the mind, as a memory of what has been or as a notion of what will be. In daily life, most of us don’t pay particular attention to the here and now with all that it implies. To capture the present, to live it and to be it is the goal of the painter who dives into the stream of thoughts forming the novel Água Viva by Clarice Lispector.

According to scientists specialised in the workings of the brain, the present lasts no longer than three seconds. Certainly, when we say “now”, we seldom think of it as such a short period of time, but language is necessarily imprecise and in addition meaning changes with context as well as with people concerned. Nonetheless, we may agree on it that the present is nothing but a fleeting moment that separates past and future… and it’s all that we actually have. Everything else only exists as an idea in the mind, as a memory of what has been or as a notion of what will be. In daily life, most of us don’t pay particular attention to the here and now with all that it implies. To capture the present, to live it and to be it is the goal of the painter who dives into the stream of thoughts forming the novel Água Viva by Clarice Lispector.Friday, 3 June 2016

Book Review: The Monkey Grammarian by Octavio Paz

by an author whose family name starts with the letter

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

When I decided to read and review The Monkey Grammarian by Octavio Paz for Guiltless Reader’s Read the Nobels 2016 challenge, I didn’t quite know what to expect. After all, my main reason to choose the book was that I liked its title and that at first sight it wasn’t poetry like most other works from the pen of this Mexican author that I saw in the bookshop. Having read that the Swedish Academy had honoured him in 1990 with the Nobel Prize in Literature “for impassioned writing with wide horizons, characterized by sensuous intelligence and humanistic integrity”, I divined – correctly – that it would be a difficult read that required much attention as well as patience. However, for me this was rather an incentive to read it than a deterrent! As it turns out, the slim book is a highly philosophical exploration of language and grammar inspired by the memories of a visit to the Hindu temples of Galta in Rajastan.

Friday, 29 April 2016

Book Review: Tierra del Fuego by Sylvia Iparraguirre

by an author whose family name starts with the letter

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z

It’s a sad fact that for centuries most Europeans looked down on indigenous peoples living in the countries that their explorers not only discovered but also conquered. How often do we find that they were treated like wild beast and some of them brought to Europe to entertain kings and queens or to show in curiosity shops. Missionaries and colonists were hardly any more understanding and open-minded towards seemingly primitive cultures. In the epistolary novel Tierra del Fuego by Sylvia Iparraguirre a fictional Anglo-Argentine seaman recounts true events from the early nineteenth century surrounding a native Patagonian who is known as Jemmy Button. As a young man he was brought from Tierra del Fuego to London to learn the basics of English civilisation and years later he was put on trial, then sentenced and executed for having played a leading role in the massacre of English missionaries in the islands.

Friday, 23 October 2015

Book Review: Of Love and Other Demons by Gabriel García Márquez

Love is a very powerful emotion that can overwhelm even the strongest and most disciplined character, especially when it comes by surprise and for the first time. Love always feels like magic, but sometimes it appears to the outsider as if a potent spell has been cast on the lovers or only one of them. When the passion is so strong that it becomes harmful and destructive to the people concerned, it isn’t a long way to think that a demon must be at work. This is what happens in the historical novel Of Love and Other Demons by Gabriel García Márquez set in a time when and a place where superstition was common. It tells a story of first love under particularly unfavourable circumstances and between a most unlikely couple, namely between a scarcely adolescent girl alleged of being possessed by demons and her already middle-aged exorcist in an eighteenth-century sea town somewhere in South America.

Wednesday, 26 November 2014

Author’s Portrait: Maria Firmina dos Reis

Already earlier this year I remarked that Brazil was a bit of a blank on my literary world map although the country is huge and counts millions of inhabitants. As a matter of fact, her literature receives little attention abroad. Maybe this is due to the fact that Brazil’s official language is the local variety of Portuguese and I noticed that translations from this language aren’t particularly present on the international book market. Despite all there are of course notable Brazilian writers apart from Paulo Coelho, contemporary as well as classic ones. There even was a nineteenth-century woman writer, moreover one with African roots, who enjoyed some renown in her time. Her name was Maria Firmina dos Reis and this portrait is dedicated to her.

Friday, 5 September 2014

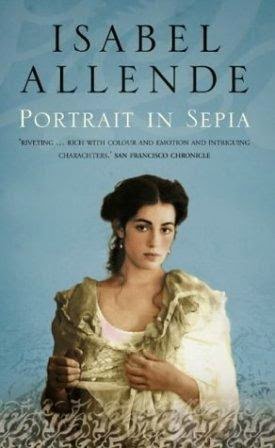

Book Review: Portrait in Sepia by Isabel Allende

Doing research on family history can be quite fascinating, especially when well-kept secrets are finally revealed or unexpectedly come to light. Consequently, it’s no wonder that genealogy is such a popular hobby these days! But however much information we gather about our ancestors, the picture that we get will never show them in their true colours. Instead it will inevitably be yellowed, probably even blurred and faded... just like the picture that we have of ourselves. The protagonist of Portrait in Sepia by Isabel Allende comes to the conclusion when she puts together the life stories of three generations that led to her existence and that made her the vague person who she is.

Doing research on family history can be quite fascinating, especially when well-kept secrets are finally revealed or unexpectedly come to light. Consequently, it’s no wonder that genealogy is such a popular hobby these days! But however much information we gather about our ancestors, the picture that we get will never show them in their true colours. Instead it will inevitably be yellowed, probably even blurred and faded... just like the picture that we have of ourselves. The protagonist of Portrait in Sepia by Isabel Allende comes to the conclusion when she puts together the life stories of three generations that led to her existence and that made her the vague person who she is.

Isabel Allende, in full Isabel Allende Llona, was born in Lima, Peru, in August 1942 into a family of Chilean diplomats and politicians. In the 1960s she worked for the United Nations, married and had children. Being the cousin of Salvador Allende, the President of Chile until the coup d’état of 1973, she fled to Venezuela following death threats. There she got into journalism and began writing fiction. The writer’s debut novel was The House of the Spirits (La casa de los espíritus) which was refused by several Latin-American publishers and became an immediate success when a Spanish publisher brought it out in 1982. Others of her notable works, which often have a strong autobiographical touch, are Eva Luna (1987), Paula (1994), Portrait in Sepia (Retrato en sepia: 2000), City of the Beasts (La ciudad de las bestias: 2002), Inés of My Soul (Inés del alma mía: 2006), and Maya's Notebook (El Cuaderno de Maya: 2011). Her latest published novel is the murder mystery Ripper (El juego de Ripper: 2014). In 1989 Isabel Allende settled down in San Rafael, California, USA, with her second husband where she still lives.

It’s thirty-year-old Aurora del Valle who puts together a Portrait in Sepia of herself with the poorly defined and incomplete pieces of information about parents and grandparents. Aurora is born in San Francisco’s Chinatown on a Tuesday morning in the autumn of 1880. Her mother is Lynn Sommers, the young, beautiful and rather dull daughter of English-Chilean Eliza Sommers and her Chinese husband Tao Chien, the community’s most renowned zhong-yi and much respected for his medical expertise by Chinese colleagues as well as western doctors. However, he isn’t able to save his daughter who dies a few hours after giving birth. Aurora’s natural father is Matías Rodrígues de Santa Cruz, the eldest son of wealthy Paulina del Valle and Feliciano Rodrígues de Santa Cruz, but he seduced Lynn following a bet with his friends and didn’t think of marrying her as she was convinced that he would because her mind was full of the cheap romances that her grandaunt Rose Sommers wrote. In his stead cousin Severo del Valle from Valparaíso in Chile, who stays with his aunt Paulina while being trained to be a lawyer, fell in love with Lynn and in the end he succeeded in persuading her to marry him to give the child his honourable name. When Lynn dies, Severo is desperate. He decides to seek death joining the Chilean army engaged in a war with Peru and Bolivia at the time and leaves Aurora with her maternal grandparents. The paternal grandmother, Paulina del Valle, who refused to take any responsibility for the illegitimate child of her son, takes it into her head to raise her granddaughter as soon as she learns that Lynn is dead, but Severo del Valle as the girl’s father before the law has left detailed instructions and neither Eliza Sommers, nor Tao Chien are willing to give Aurora up.

Five years pass and one day Eliza Sommers shows up at the residence of Paulina del Valle with Aurora to leave her there because her husband was killed and she needs to take care of his funeral in Hong Kong. Paulina del Valle, who has been widowed for a couple of months too, is delighted to get her will at last and to raise the girl. She decides to sell her house in San Francisco and to return to her native Chile after a tour of Europe to distract the fearsome girl who is haunted by nightmares. Before leaving, Paulina’s loyal major-domo of many years, Frederick Williams, proposes to her and she accepts the marriage of convenience with the man who will pass as a British noble from then on. In 1886 they arrive in Santiago where Severo del Valle has meanwhile recovered from the loss of a leg, married his incredibly fertile cousin Nívea and settled down as a lawyer. Aurora stays with her grandmother and growing up witnesses the turmoil of recurring revolutions and civil wars in Chile.

Already the first sentence of Portrait in Sepia reveals that the protagonist herself sets out to tell the story of her life and of her origins as far as she managed to find them out. Isabel Allende skilfully embedded the crude facts of personal history into picturesque and lively images. At the same time the author dwelled in several clichés like just for instance teenage girls who blindly run after their loved ones leaving behind their families, even countries without a second thought and a much idolized young beauty who is empty-headed and seduced by a spoilt young man from a respected family. Such stereotypes use to annoy me because repeating them means keeping them alive, even when they are believed to be long outdated. Fortunately, Isabel Allende made the main female characters, notably Paulina del Valle, Severo del Valle’s wife Nívea and the protagonist herself, strong, intelligent and active women. All in all the novel is a slow-paced first-person narrative which unfolds for the greatest part chronologically and which is always interweaved with the true historical background. Not being a historian, nor otherwise well acquainted with the history of California and Chile from 1862 through 1910, I dare not to judge whether everything is based on thorough research, but at least I didn’t stumble across any obvious inconsistencies. The language of Isabel Allende is rich in colourful images and yet unpretentious. It’s also sufficiently simple for me to be able to enjoy reading the Spanish original.

I admit that Portrait in Sepia by Isabel Allende probably isn’t the most intriguing and worthwhile work of this enormously popular Chilean author, but I still took great pleasure in the read. Moreover, it gave me an idea of the turbulent history of Chile which is quite a lot considering that I knew virtually nothing about it. And it goes without saying that I recommend the book to you.

Five years pass and one day Eliza Sommers shows up at the residence of Paulina del Valle with Aurora to leave her there because her husband was killed and she needs to take care of his funeral in Hong Kong. Paulina del Valle, who has been widowed for a couple of months too, is delighted to get her will at last and to raise the girl. She decides to sell her house in San Francisco and to return to her native Chile after a tour of Europe to distract the fearsome girl who is haunted by nightmares. Before leaving, Paulina’s loyal major-domo of many years, Frederick Williams, proposes to her and she accepts the marriage of convenience with the man who will pass as a British noble from then on. In 1886 they arrive in Santiago where Severo del Valle has meanwhile recovered from the loss of a leg, married his incredibly fertile cousin Nívea and settled down as a lawyer. Aurora stays with her grandmother and growing up witnesses the turmoil of recurring revolutions and civil wars in Chile.

Already the first sentence of Portrait in Sepia reveals that the protagonist herself sets out to tell the story of her life and of her origins as far as she managed to find them out. Isabel Allende skilfully embedded the crude facts of personal history into picturesque and lively images. At the same time the author dwelled in several clichés like just for instance teenage girls who blindly run after their loved ones leaving behind their families, even countries without a second thought and a much idolized young beauty who is empty-headed and seduced by a spoilt young man from a respected family. Such stereotypes use to annoy me because repeating them means keeping them alive, even when they are believed to be long outdated. Fortunately, Isabel Allende made the main female characters, notably Paulina del Valle, Severo del Valle’s wife Nívea and the protagonist herself, strong, intelligent and active women. All in all the novel is a slow-paced first-person narrative which unfolds for the greatest part chronologically and which is always interweaved with the true historical background. Not being a historian, nor otherwise well acquainted with the history of California and Chile from 1862 through 1910, I dare not to judge whether everything is based on thorough research, but at least I didn’t stumble across any obvious inconsistencies. The language of Isabel Allende is rich in colourful images and yet unpretentious. It’s also sufficiently simple for me to be able to enjoy reading the Spanish original.

I admit that Portrait in Sepia by Isabel Allende probably isn’t the most intriguing and worthwhile work of this enormously popular Chilean author, but I still took great pleasure in the read. Moreover, it gave me an idea of the turbulent history of Chile which is quite a lot considering that I knew virtually nothing about it. And it goes without saying that I recommend the book to you.

Labels:

2000s,

book reviews,

fiction,

Latin American literature,

novels

Friday, 20 June 2014

Book Review: The Decapitated Chicken by Horacio Quiroga

This week I’m turning my attention to the southern hemisphere and to a master of short fiction who is often referred to as the “Latin-American Edgar Allan Poe”: Horacio Quiroga. At first I intended to review his Cuentos de amor de locura y de muerte, but to my great regret I found out that this original short story collection has never been translated into English, at least not in its entirety. Considering the fame that the author again enjoys in South America almost eighty years after his tragic death, it seems quite strange to me that only so few of his short stories are available in English translation. A dozen of them has been brought together in the anthology The Decapitated Chicken and Other Stories by Horacio Quiroga which I’m reviewing today.

This week I’m turning my attention to the southern hemisphere and to a master of short fiction who is often referred to as the “Latin-American Edgar Allan Poe”: Horacio Quiroga. At first I intended to review his Cuentos de amor de locura y de muerte, but to my great regret I found out that this original short story collection has never been translated into English, at least not in its entirety. Considering the fame that the author again enjoys in South America almost eighty years after his tragic death, it seems quite strange to me that only so few of his short stories are available in English translation. A dozen of them has been brought together in the anthology The Decapitated Chicken and Other Stories by Horacio Quiroga which I’m reviewing today.

Horacio Quiroga, in full Horacio Silvestre Quiroga Forteza, was born in Salto, Uruguay, in December 1878. Towards the end of the nineteenth century he began writing for papers and literary journals and already in 1901 he compiled the best stories and poems in his first book, Los arrecifes de coral (Coral Reefes). His private life was shadowed by dramatic blows of fate and recurring financial problems. To earn his living he ran plantations in the jungle that he loved, worked as a Castillian teacher and later as an employee of the Uruguayan consulate in Buenos Aires, while he continued to write prolifically. With The Feather Pillow (El almohadón de pluma) published in 1907 Horacio Quiroga achieved mastery and first fame as a short story writer. Along with several short story collections – most famous among them Cuentos de amor de locura y de muerte (1917; Stories of Love of Madness and of Death), Cuentos de la selva (1918; Jungle Tales) for children and Los desterrados (1926; Exiles) – he wrote two novels and a play which weren’t successful, though. At the age of fifty-eight Horacio Quiroga was diagnosed with incurable prostate cancer and committed suicide in the hospital in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in February 1937.

The scenery of The Decapitated Chicken and Other Stories is the author’s South America, above all the Argentine provinces Chaco and Misiones on the river Paraná, but also Buenos Aires. The opening story is The Feather Pillow (El almohadón de pluma: 1907) which revolves around a mysterious illness draining life from a young married woman in her new home. In Sunstroke (La insolación: 1908) a puppy watches the unreasonable behaviour of its master under the burning sun of Argentinean summer. The Pursued (Los perseguidos: 1908) are two young men who meet in Buenos Aires. One had suffered paranoid episodes after typhoid fever, but had learnt to keep his fear and imagination under control, while the other is so highly sensitive and excitable that he on his part feels pursued by his new paranoid friend. The title story of the English-language anthology (which is not a translation of the original collection under the title of the same story), The Decapitated Chicken (La gallina degollada: 1909), is about the married couple Mazzini-Ferraz and their four mentally handicapped sons. After several years a girl is born to them and they neglect the boys leaving them in the care of their servants. The boys use to pass their days seated on a bench in the patio with the eyes fixed on the bricks of the enclosure before them. When they watch a servant in the kitchen behead a chicken for dinner, the vivid red of the blood fascinates them and drives them to commit a horrible deed. In the following story, Drifting (A la deriva: 1912), a man is bitten by a venomous snake and takes the canoe to seek help in town five hours down the river. A Slap in the Face (Una bofetada: 1916) of a seemingly meek indigenous worker is the final act to make him plan his cruel revenge on the tyrannical boss. The protagonist of In the Middle of the Night (En la noche: 1919) is a woman rowing tirelessly, but in vain against the current of the Paraná. Juan Darién (1920) is a tiger who is raised as if he were a boy and who eventually turns his back on human society in disgust. In The Dead Man (El hombre muerto: 1920) the hard-working protagonist has a fatal accident with a machete and refuses to accept that all his efforts have been wasted. Anaconda (1921) is a short novellette about a union between venomous and other snakes living in the jungle who want to protect their habitat from human destruction. The Incense Tree Roof (El techo de incienso: 1922) is about the rather chaotic chief of the local Registrar’s Office who needs to bring in order the registries of four years after an inspection. In the closing story The Son (El hijo: 1935) a man lies dying in the jungle fully aware that his two sons are too young to survive there on their own.

The atmosphere of The Decapitated Chicken and Other Stories is more or less bleak and disgusting in the tradition of Edgar Allan Poe. The strong impression that the work of the latter and also of Guy de Maupassant and Rudyard Kipling left on Horacio Quiroga is obvious in his writings although they are salted with a distinctly South American touch and certain aspects like mysterious and recurring tragedy or detailed description of sensory perception which foreshadow the magical realism of Jorge Luis Borges, Gabriel García Márquez and other writers of this literary movement. Among the twelve short stories in the present anthology there are at least three children’s stories, namely Sunstroke, Juan Darién and the short novellette Anaconda, which are all set in the jungle with animal protagonists, namely a puppy, a tiger and a snake, and which are written in a colloquial language reminding of fairy tales and fables. There he criticises the unreasonable and destructive behaviour of men, notably in the jungle. However, the narrative domain of Horacio Quiroga is the morbid, the cruel and the perverse, a fact that mirrors the author’s own life marked by so many tragic incidents that reading his biography almost makes think of the old-testamentary Book of Job. In his best stories he doesn’t even need to be explicit about the horrible facts, but mere insinuations suffice to make the flesh creep. In the chronologically arranged collection the development of the writer becomes very obvious. I read all stories in Spanish although some of the – luckily not too numerous – South American expressions were a bit of a challenge.

Since The Decapitated Chicken and Other Stories isn’t based on any of the original compilations edited by Horacio Quiroga himself (without identifiable order), I had to search for the individual stories. In the end I managed to lay hands on a most beautiful Spanish-language edition (out of stock, lamentably) which I don’t want to leave unmentioned, namely Horacio Quiroga: Cuentos, third edition 2004, published by Biblioteca Ayacucho in Caracas, Venezuela. It contains all the twelve short stories from the reviewed English-language anthology and many more, plus a very interesting introduction by Emir Rodríguez Monegal.

Since The Decapitated Chicken and Other Stories isn’t based on any of the original compilations edited by Horacio Quiroga himself (without identifiable order), I had to search for the individual stories. In the end I managed to lay hands on a most beautiful Spanish-language edition (out of stock, lamentably) which I don’t want to leave unmentioned, namely Horacio Quiroga: Cuentos, third edition 2004, published by Biblioteca Ayacucho in Caracas, Venezuela. It contains all the twelve short stories from the reviewed English-language anthology and many more, plus a very interesting introduction by Emir Rodríguez Monegal.

The original Spanish versions of Horacio Quiroga’s short stories are all in the public domain. Only one title by this author can be found on the Project Gutenberg site, but many more are available on Spanish sites providing free e-books.

On the whole, The Decapitated Chicken and Other Stories by Horacio Quiroga was a very fascinating, though sometimes unpleasant read for me since I’m not a huge fan of horror and cruelty in literature. However, not all stories are creepy and in small doses I can bear with it. In brief, it definitely was worthwhile reading those almost secret gems of Latin-American literature. My verdict: recommended to those who like the genre.

Friday, 4 April 2014

Book Review: The Three Marias by Rachel de Queiroz

Brazil hosts the FIFA World Cup (soccer) in June/July. Not that it mattered to me! Sports don’t figure at all in my diverse fields of interest, but the unavoidable publicity for the event drew my attention to the country and I realised that I knew next to nothing about her literature. The only Brazilian author who came into my mind was Paulo Coelho and I reckon that I’m not the only one who is painfully ignorant of the gems that Brazilian literature has to offer. Certainly this lacuna in my reads is partly owed to the fact that translations aren’t easy to find. So I decided to do some research and finally picked for this week’s review a Brazilian classic which is on many school reading lists and which is available in English: The Three Marias by Rachel de Queiroz.

Rachel de Queiroz was born in Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil, in November 1910. As from 1927 she worked mainly as a journalist for different newspapers writing very popular chronicles, but also dedicated herself to fiction. Her first novel, O Quince, came out in 1930 and was received with immediate acclaim. Other novels followed: João Miguel (1932), O caminho das pedras (1937), The Three Marias (As três Marias: 1939), O galo de ouro (1950), Dora Doralina (1975), and Memorial de Maria Moura (1992). Rachel de Queiroz died in Leblon, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in November 2003 shortly before turning 93 years old.

It’s Brazil in the 1930s. In the beginning of The Three Marias the narrating protagonist, Maria Augusta called Guta, is a twelve-year-old girl, a sensitive and fearful child used to carefree country life. It’s her first day in the boarding school attached to a Roman Catholic convent in Fortaleza and the austere atmosphere intimidates her from the start. Despite all she quickly finds friends, but it’s her class mate Maria José who takes the initiative and introduces her to the other girls. Before long they form a party of three with Maria Glória. One of the nuns jokingly refers to them as the Three Marias which is how the three stars of the Orion’s Belt are called in Brazil. The life of the girls in boarding school is strictly regulated and at least as secluded as that of the nuns. Guta feels encaged and shut out of life. She suffers under the harsh conditions, sheds many tears and is full of fears that make her consider suicide sometimes. Time passes and the girls grow up with the romantic ideals that they find in cheap novels and the small or big scandals that their hunger for life and love provokes. Soon school years are over and the now eighteen-year-old girls are sent out into the world to deal with real life. The three Marias return to their respective families, but Guta can’t bear the regulated routine of home where she feels like a stranger. She convinces her father to allow her to go back to Fortaleza to attend a typing course and earn her living as a typist there. At last she is free! Free to come to know the world and the ways of men. Raul, a horny aging painter of some renown, Aluísio, a melancholic young men who doesn’t dare revealing his love to Guta, and Isaac, a Jewish physician from Greece who has to pass exams to have his degree recognized in Brazil and to be allowed to stay, court Guta, while Maria Glória makes a happy marriage and Maria José turns into a devout teacher fearing for everybody’s soul.

Quite obviously the first-person narrative titled The Three Marias is a coming-of-age novel and my German edition calls it “the best and most entertaining women’s fiction of Brazilian literature”. Well, there’s definitely some truth in the latter although I don’t like the label at all. In any case, Rachel de Queiroz’s novel made quite a stir when it first came out in 1939! Just imagine strictly Catholic Brazilians reading a book in which the female protagonist handles men without the caution that six years of convent boarding school should have instilled into her and also without always having marriage in the back of her mind, moreover a book written by a woman of only twenty-nine. And yet, it cannot be said that Rachel de Queiroz advocated shameless behaviour or talked openly about sex. On the contrary, the author’s language is very decent and oblique by today’s standards. Often she only slightly hints at what happens. The story itself, of course, isn’t as innocent as moralists would wish it to be, above all towards the end. In addition, the author displays the full scale of social reality in the 1930s without closing her eyes before the improper and the unpleasant. Prostitutes, illegitimate and orphaned children, an eloping couple, a hard-drinking husband, a blind baby, an abandoned worn-out wife and mother,… they all make a background appearance in this novel.

When I found out that The Three Marias by Rachel de Queiroz was a coming-of-age novel, I wasn’t quite sure if I would really wish to review it. At my age I’m not easily intrigued by such reads, but this one definitely gives an interesting insight into the mind of a young woman and after all I already reviewed other novels of the kind. Nada by Carmen Laforet (»»» see my review) can’t really be compared to this one because it has a different focus and as for Bonjour Tristesse by Françoise Sagan (»»» see my review), I liked this Brazilian novel even better. In a nutshell, The Three Marias by Rachel de Queiroz deserves much more attention.

Friday, 1 March 2013

Book Review: The Way to Paradise by Mario Vargas Llosa

In his biographical novel The Way to Paradise the Peruvian writer and Nobel Prize laureate Mario Vargas Llosa displays the lives of the French trade unionist and early women’s rights activist Flora Tristán (7 April 1803 – 14 November 1844) and of her famous grand-son, the post-impressionist painter Paul Gauguin (7 June 1848 – 8 May 1903). The author highlights the common traits of their character as well as their search for the ideal and free life. When I first read the historical novel a few years ago, I was quite impressed by the double biography of those two outstanding and strong characters, so it seemed obvious to me to review it here.

In his biographical novel The Way to Paradise the Peruvian writer and Nobel Prize laureate Mario Vargas Llosa displays the lives of the French trade unionist and early women’s rights activist Flora Tristán (7 April 1803 – 14 November 1844) and of her famous grand-son, the post-impressionist painter Paul Gauguin (7 June 1848 – 8 May 1903). The author highlights the common traits of their character as well as their search for the ideal and free life. When I first read the historical novel a few years ago, I was quite impressed by the double biography of those two outstanding and strong characters, so it seemed obvious to me to review it here.Mario Vargas Llosa was born in Arequipa, Peru, in March 1936. Already as a teenager he took to writing and worked as a freelance journalist for local newspapers. While studying law and literature at the National University of San Marcos in Lima, Peru, he began to pursue his literary ambitions more seriously. His first short stories were published. For two years Mario Vargas Llosa continued his studies at the Complutense University of Madrid, Spain, and moved on to Paris in 1960 where he started to write with more verve. His first novel, The Time of the Hero (La ciudad y los perros), came out in 1963 and was an immediate success. In 1966 The Green House (La casa verde) followed receiving even more acclaim and being considered the finest as well as the most important of Mario Vargas Llosa’s novels up to the present day. During the following decades the prolific author brought out a new novel every three to four years along with non-fiction work. The Way to Paradise (El paraíso en la otra esquina which in Spanish is the name of a children’s game, by the way) was first released in 2003. In 2010, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for his life’s work. Mario Vargas Llosa died in Lima, Peru, in April 2025.

The Way to Paradise starts in April 1844 in a room in Paris, France, when Flora Tristán awakes at four o’clock in the morning, the day when she travels to Auxerre where she’s expected to give a trade unionist speech. Memory takes her back to her childhood. As the illegitimate child of a rich Peruvian she grew up in Paris with her poor French mother whom she despised for her miserable existence and for giving her away to the first man who wanted to marry her, the owner of the graphics and lithography workshop where she had been an apprentice, a syphilitic and violent drunkard without any respect for women. Paul Gauguin’s story, too, is told mainly through flashbacks and streams of consciousness. The account begins in Mataiea, Marquesas Islands, in 1892, when the painter had already been living in the Pacific Islands for a couple of years. In the novel the lives of Flora Tristán and her famous grand-son are interweaved although in reality they never met as Flora Tristán died before her grand-son was born. Alternating their stories throughout the twenty-two chapters of the novel, Mario Vargas Llosa shows the parallels of their respective flight from the social conventions of their time. Flora Tristán left her husband and devoted her entire life to the fight for women’s rights, workers’ rights and socialism. Paul Gauguin gave up his comfortable existence and his family in France in order to be a painter who seeks inspiration not only abroad, but also in sexual excesses with often very young Polynesian women. Their longing for freedom implied that they both had to face many struggles and hardships along with failing health caused by syphilis.

Overall The Way to Paradise gives an interesting insight into the character of those two historical figures who themselves never arrived in paradise, but inspired others to follow their way and continue their strivings for an ideal life and society. I’m not in the position to judge the historical accuracy of the novel, to me it seems close enough to the facts, though, and it introduced me to Flora Tristán who I had never heard of before. The narrative is written in a style that can capture readers like me and that shows that the author was an experienced one who knew what he did.

At any rate, I enjoyed reading the book very much although critics say that in this novel Mario Vargas Llosa didn’t show his usual genius. I can’t judge it since The Way to Paradise is the only work of Mario Vargas Llosa that I know so far. Besides, there’s no accounting for tastes, is there?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)