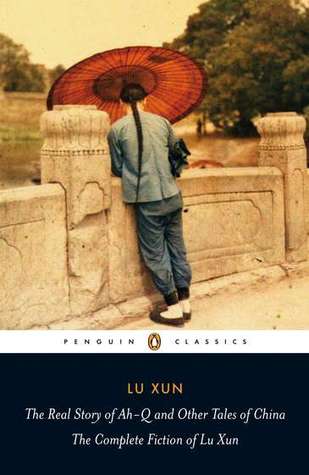

China is a vast country with an ancient culture, and yet, only few books from the pens (or rather brushes) of Chinese writers have made it into Western bookshops. This is little wonder considering that China has been a Communist country since 1949 and only after the death of Mao Zedong intellectual life slowly reawakened. There are some contemporary authors who have gained international attention, notably the laureate of the Nobel Prize in Literature 2012 Mo Yan. Among modern classical writers of the twentieth century Eileen Chang may be the best remembered (»»» read my review of Red Rose, White Rose), while others like Lin Yutang or Xiao Hong are quite forgotten today. Notwithstanding that a new English translation has been brought out in 2009, also The Real Story of Ah-Q and Other Tales of China by Lu Xun have remained secret gems of Chinese literature evoking the 1920s and ancient myths.

China is a vast country with an ancient culture, and yet, only few books from the pens (or rather brushes) of Chinese writers have made it into Western bookshops. This is little wonder considering that China has been a Communist country since 1949 and only after the death of Mao Zedong intellectual life slowly reawakened. There are some contemporary authors who have gained international attention, notably the laureate of the Nobel Prize in Literature 2012 Mo Yan. Among modern classical writers of the twentieth century Eileen Chang may be the best remembered (»»» read my review of Red Rose, White Rose), while others like Lin Yutang or Xiao Hong are quite forgotten today. Notwithstanding that a new English translation has been brought out in 2009, also The Real Story of Ah-Q and Other Tales of China by Lu Xun have remained secret gems of Chinese literature evoking the 1920s and ancient myths. Lu Xun (魯迅) was born Zhou Zhangshou (周樟壽) in Shaoxing, Zhejiang, China, in September 1881. He changed his name to Zhou Shuren (周樹人) in Nanjing where he received a Western education. After graduation, he moved to Japan to study Western medicine, but soon turned his attention to literature as means for cultural reform. Back in China, he worked as teacher in secondary schools and colleges until securing a job in the Ministry of Education. Although he wrote his first short story Nostalgia (懷舊) already in 1911 (secretly published by his brother in 1913), he dared his literary debut only in 1918 with Diary of a Madman (狂人日記) adopting the pen name Lu Xun. He compiled his short stories in Call to Arms (吶喊: 1923) and followed up with two more collections, namely Wandering (彷徨: 1925) and Old Tales Retold (故事新編: 1935) that have been released together in a new English edition entitled The Real Story of Ah-Q and Other Tales of China. The author also published 中國小說史略 (1925; A Brief History of Chinese Fiction), the prose poetry collection Wild Grass (野草: 1927) and essays, many of them comprised in Dawn Blossoms Plucked at Dusk (朝花夕拾: 1932). Lu Xun died in Shanghai, China, in October 1936.

The actual text of The Real Story of Ah-Q and Other Tales of China begins with Lu Xun’s very first short story Nostalgia that evokes a typical gentry childhood in the care of a private tutor well-versed in the Chinese classics. In the following, all three of the author’s short story collections are reproduced in chronological order. The first is Outcry (previously translated as Call to Arms) consisting of a preface and fourteen stories. In Diary of a Madman a delirious man comes to believe that he lives among cannibals and that his brother too wants to eat him.

“Avoid overexcitement! Rest! Of course: they want to fatten me up, so there will be more to go round. ‘You’ll be fine’? They were all after my flesh, but they couldn’t be open about it – they had to pursue their prey with secret plans and clever tricks; […]The Real Story of Ah-Q, on the other hand, recounts the fate of an illiterate labourer who ruins his life bluntly asking a woman to sleep with him. The eleven stories of Hesitation (previously translated as Wandering) follow in the same line depicting rural and small-town life in 1920s China. New Year’s Sacrifice, for instance, deals with a maidservant who has fallen into disgrace because twice widowed and robbed of a son by the wolves her mistress fears that she brings bad luck over the household if she touches anything to do with the sacrifice. The protagonist of The Loner loses his livelihood as a teacher after publishing articles in which he expressed his strong views, becomes the much respected aide to a local warlord – and suddenly dies.

[…] ‘To be eaten immediately!’ the old man muttered as he left. My brother nodded. Et tu! And yet I should have foreseen it all: my own brother in league with people who wanted to eat me!”

“[…] When I asked to see the deceased, they did their best to turn me back, claiming that I did them ‘too much honour’. In the end, though, I persuaded them, and the curtain was opened.As the title Old Stories Retold indicates, in his final collection the author dedicated himself to Chinese legends and myths. Mending Heaven is about Goddess Nüwa’s efforts to fill a crack in the sky with stones and smelt them together, while the protagonist of Forging the Swords is fifteen-year-old Mei Jianchi who sets out to avenge his father whom the king killed as “reward” for having forged a magical, i.e. invincible sword for him.

Lianshu lay before me, in death. And yet, the strangest thing! Despite his crumpled shirt and trousers, the bloodstains on the lapels, the hideous emaciation of his face – despite all this, his face essentially remained as it had always been, his mouth and eyes peacefully shut as if in sleep. I almost reached out to place my hand over his nose, to check whether he was still breathing.”

That translator Julia Lovell calls her collection of Lu Xun’s complete short fiction The Real Story of Ah-Q and Other Tales of China of China seems appropriate considering that the texts either portray Chinese life like in the most famous story highlighted in the title or they reinterpret ancient legends and myths. However common the stories may appear to Western readers, the more innovative it was for a Chinese author of the 1920s to transform his own experience and observations into fiction, much of it written in first-person. This approach to story-telling and the use of simple vernacular rather than classical Chinese served a purpose, though. Lu Xun used his art to criticise, to instruct, to reform, in other words to build a new China less hampered by tradition and Confucianism. This is at the same time a strength and a flaw of his work because moralising adds a dimension to realism while limiting its range. Long after the author’s death his clearly socialist sympathies allowed Mao Zedong to celebrate him as model Communist writer, a fact that compromises his work today. The translator’s Introduction and notes as well as the Afterword by Chinese-American writer Yiyun Li help to understand Lu Xun’s world.

Without doubt it was an interesting and enjoyable experience to read The Real Story of Ah-Q and Other Tales of China by Lu Xun, not least thanks to the excellent English translation. Despite all, I must admit that I was a little disappointed too because all things considered, the stories of the so much praised author seemed pretty ordinary and even shallow to me. Still, they are fascinating time pieces allowing brief glimpses into the lives of common people in China during the turbulent years from the late nineteenth century through the mid-1920s , but the view is the biased one of a writer with socialist ideas who wished to lead Chinese society into modern times with the help of popular literature. The ancient legends and myths were more in my line, at the same time different from our Western ones and yet familiar in a way. Altogether it was a read that deserves my recommendation.

* * * * *

This review is a contribution to

(images linked to my reading lists):

(images linked to my reading lists):

So interesting. I was just this morning reading a review of Can Xue's most recently translated novel, Frontier. It got me to wondering how possible it is for an American or Western person to understand such a vast and different country as China merely by reading fiction written there. I suppose it is better than nothing if one cannot go there.

ReplyDelete