A hundred years ago, in 1915, the Young Turk government, that had seized power in the Ottoman Empire in 1908, took advantage of the chaos of World War I to get rid of the Armenian population living in Eastern Anatolia. Thanks to the foot marches of several days with hardly any provisions the deportation to concentration camps in the Mesopotamian desert meant almost certain death from exhaustion and hunger – provided that people weren’t killed on the way by scoundrels seething of hatred and greed or even by their guards. However, six Armenian villages in the Syrian Hatay Province revolted against expulsion seeking refuge on Musa Dagh (Mount Moses), a natural fortress at the Gulf of Alexandrette, and a major work of Austrian literature, namely The Forty Days of Musa Dagh by Franz Werfel which I’m reviewing today, gives fictional testimony of the events until the last-minute rescue of 4,200 men, women and children by French and British warships.

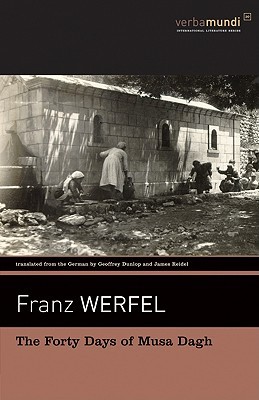

A hundred years ago, in 1915, the Young Turk government, that had seized power in the Ottoman Empire in 1908, took advantage of the chaos of World War I to get rid of the Armenian population living in Eastern Anatolia. Thanks to the foot marches of several days with hardly any provisions the deportation to concentration camps in the Mesopotamian desert meant almost certain death from exhaustion and hunger – provided that people weren’t killed on the way by scoundrels seething of hatred and greed or even by their guards. However, six Armenian villages in the Syrian Hatay Province revolted against expulsion seeking refuge on Musa Dagh (Mount Moses), a natural fortress at the Gulf of Alexandrette, and a major work of Austrian literature, namely The Forty Days of Musa Dagh by Franz Werfel which I’m reviewing today, gives fictional testimony of the events until the last-minute rescue of 4,200 men, women and children by French and British warships. Franz Werfel was born into a German-speaking Jewish family in Prague, Bohemia, Austria-Hungary (today: Czech Republic), in September 1890. Early he discovered his love for writing and in 1911 his first volume of poetry, Der Weltfreund (The Philanthropist), was released. In 1912 he moved to Leipzig, Germany, to work as an editor for a new publisher until he was called up to serve in the Austro-Hungarian army in 1915. Towards the end of World War I Franz Werfel was introduced to Alma Mahler, then married to Walter Gropius, who soon became his lover and many years later his wife. A volume of war poems appeared in 1919 under the title Der Gerichtstag (The Day of Judgement) and was followed by some highly successful plays, but the author’s lasting fame is based above all on his novels and short stories. The most important among them are Verdi. Novel of the Opera (Verdi. Roman der Oper: 1924), Class Reunion (Der Abituriententag: 1928), The Forty Days of Musa Dagh (Die vierzig Tage des Musa Dagh: 1933), The Song of Bernadette (Das Lied von Bernadette: 1941), and Pale Blue Ink in a Lady's Hand (Eine blassblaue Frauenschrift: 1941). Since he was a Jewish author his books were soon banned by the Nazi regime and in 1938 the German annexation of Austria forced him into exile. Franz Werfel died in Beverly Hills, California, United States, in August 1945. The author’s only science-fiction novel, Star of the Unborn (Stern der Ungeborenen: 1946), was published posthumously.

The story of The Forty Days of Musa Dagh begins in the dawn of World War I. Accompanied by his wife Juliette and his teenage son Stephan the Armenian scholar Gabriel Bagradian travels from Paris to Istanbul to settle the affairs of the thriving family business. Then war is declared in Europe and as Ottoman citizens Gabriel Bagradian – who always refused to apply for naturalisation in France – and his France-born family are now enemies of the French nation which prevents them from returning to their home in Paris. Like most people they believe, though, that the war will be over soon and until then they intend to live in the old country house of the Bagradians in the Armenian village of Yoghonoluk where Gabriel was born and passed his early childhood. Before long it startles him that neither he, a highly decorated reserve officer of the Ottoman army, nor any other Armenian is called to the weapons. When passports as well as teskerés (i.e. the official documents allowing free movement within the country) of his entire family and other Armenians are seized, he becomes truly alarmed. Gabriel Bagradian makes enquiries and realises that the authorities prepare another atrocious blow against Armenians. Secretly he begins to plan resistance destining the natural fortress of Musa Dagh for refuge of the population of the valley’s seven villages. His fears are confirmed by Protestant pastor Aram Tomasian, his pregnant wife Hovsannah, his younger sister Iskuhi, and two feeble-minded followers who turn up more dead than alive in Yoghonoluk. They have been deported from the city of Zeitun with the rest of the Armenian population, but escaped from the death march to the Mesopotamian desert thanks to the intervention of an American pastor in Marash and made their way to their father’s house on the Syrian coast. Weeks later the deportation order for Yoghonoluk and the other villages arrives and the time of Gabriel Bagradian has come. He convinces the major part of the villagers to join him in his fight on the Musa Dagh instead of going into a miserable death from exhaustion or hunger in road ditches or from the hands of their armed guards and of marauders looking for material as well as human booty. On the mountain plateau the desperate, though successful fight against by far superior Ottoman forces and limited resources begins under military leadership of Gabriel Bagradian. It lasts for forty days until British-French cruisers rescue the defenders.

Although The Forty Days of Musa Dagh is based on the true story of the people of Yoghonoluk and the neighbouring villages, it is only the fictional account of historical events of which Franz Werfel first heard during his travel to the Middle East in 1930, thus fifteen years later. The author certainly performed thorough research before setting out to write his monumental novel of over 900 pages from the point of view of an omniscient third-person narrator. The scenery of Musa Dagh and its surroundings is clearly modelled after nature (even though I must admit that I haven’t been there), but none of the Armenians in the novel existed as described. Most importantly the real military leader of the defence was called Moses Derkalousdian, not Gabriel Bagradian, and probably he wasn’t a man estranged from his origins because he passed most of his life in France. Moreover Moses Derkalousdian lived to be 99 years old and didn’t die on Musa Dagh like his literary counterpart and the defenders really resisted the Ottoman troops during more than fifty, not just forty days. In his novel Franz Werfel also evokes the situation of European Jews in the early twentieth century to a certain degree and the events in Eastern Anatolia seem to foreshadow the holocaust which was to come only after the book was published in 1933, the year when Adolf Hitler seized power in Germany. Another striking parallel is that the Armenians of the novel are hated less for their (Christian) religion than for the (assumed) prosperity and financial power of their merchants, artisans and scholars. Well, the Armenian genocide hasn’t been the first in history and the holocaust wasn’t the last. Despite all, the Turkish government still seems to believe that it would be a terrible disgrace for the entire Turkish nation to admit the Armenian genocide of 1915 although – in my opinion as an Austrian familiar with the history of the holocaust and my country’s inglorious part in it – it is much more shameful, even harmful to deny and play it down. Maybe a new generation of Turkish politicians will have the courage to see things as they actually were.

As you can imagine, The Forty Days of Musa Dagh by Franz Werfel has been a very impressive and touching read despite the novel’s slightly old-fashioned German. I’m really happy to have made up my mind to review it on this blog and to re-read it to this end after almost ten years. Luckily, a revised English edition including all the passages that seem to have been omitted in the first translation of 1934 has come out in 2012. If you can get a copy, I warmly recommend you to read it. It’ll take you quite some time to get through its almost 900 pages, but it’s definitely worth it!

* * * * *

This review is a contribution to the Back to the Classics Challenge 2015, namely to the category Very Long Classic.

This review is a contribution to the Back to the Classics Challenge 2015, namely to the category Very Long Classic.»»» see my sign-up post with the complete reading list.

Bravo for you nice review!

ReplyDeleteThank you!

Delete